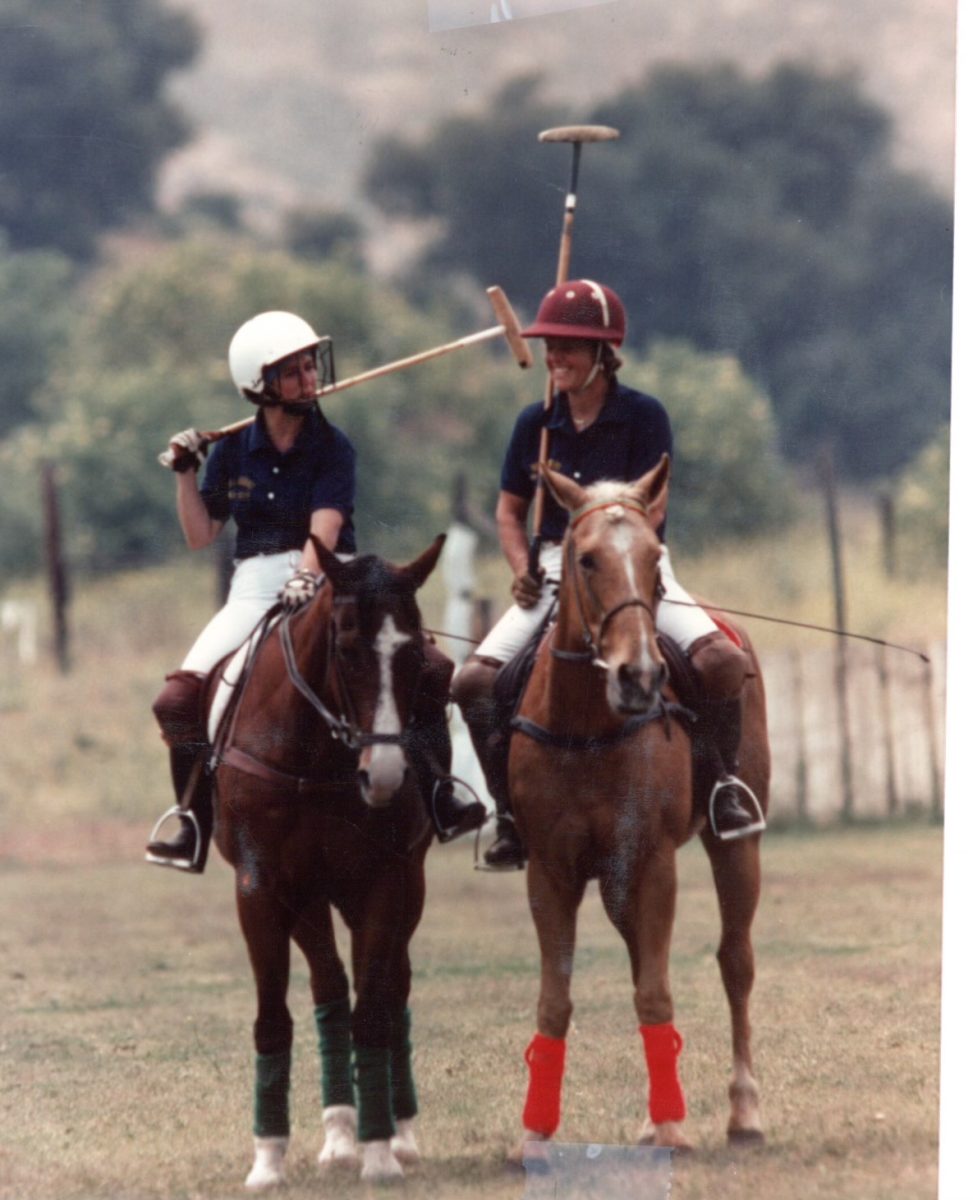

Polo is mostly depicted in the media as being strictly for rich people, specifically rich men. However, polo is a sport for everyone, not just the rich or men. Sunset “Sunny” Hale was the best female polo player in the world. She is also the first professional woman to play—and win—the US open, an annual tournament held by the United States Polo Association.

Hale passed away in 2017 after a battle with breast cancer. She is most well known for winning the US open on a team of all men, against all men, as well for being the first woman to receive a 5–goal handicap rating. In 2005, Hale created the Women’s Championship Tournament, the largest women’s polo league in the world.

“At such a young age she had accomplished so much,” said WHS student Ace Parkan ‘27. “You can tell that she dedicated herself to this sport, and really cares not just about her right[s] as a woman, but the rights of the other women who wanted to play polo.”

Hale’s mother, Sue Sally Hale, was the first to break the gender barrier in polo. After disguising herself as a boy for 20 years, she was able to play in numerous tournaments before finally revealing herself in 1972. She later went on to open her own polo club with close friend Patty Akkad.

“Buying the land and setting that up wasn’t hard, the hardest part was becoming a member of the United States Polo Association,” Akkad. “They didn’t recognize [female] players, and no woman had ever owned a polo club recognized by the USPA. By chance, I had a friend whose husband was on the board of directors. I told him, ‘If there is any legal reason a woman can’t own a polo club, tell me, and I’ll accept it.’ Then, I became the first woman to own a polo club.”

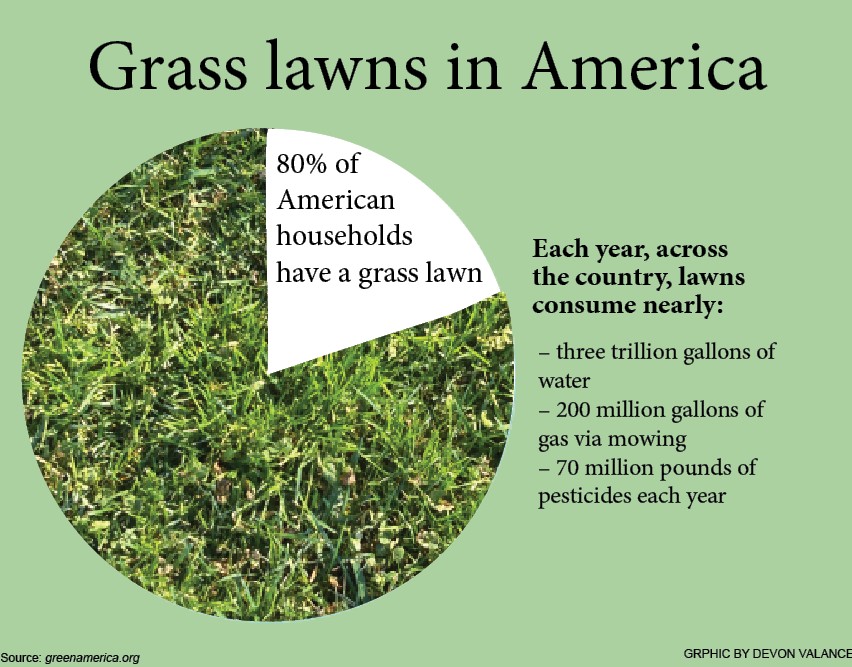

When most think of polo clubs, the image of long fields of grass, a large clubhouse, expensive cars and trailers with 25 horses a player comes to mind. However, most polo clubs and teams in America are very affordable.

“Most polo clubs in the US are small family clubs,” said Akkad. “You can have just one horse and learn to play on that one horse. [My club] wasn’t just for rich people, you didn’t have to travel and play in Palm Beach or in Santa Barbara. You could just play. You didn’t need money, you just had one horse, took care of it and played on the weekends. Sure, very rich people can have 25 horses and sponsor great players, but it’s not necessary.”

Despite the common misconception about the sport, many believe that polo can be enjoyed by everyone, including college students. Schools like Cal Poly State University, Oregon State University, the University of California Santa Barbara, Yale University and the University of Southern California all have polo teams.

“For me, it was just the luck of the draw that USC has a team, so I went there and I signed up,” said Shannon Hill, USC alumna and Westlake resident. “It’s easier for people who are in college because you can find colleges who have a polo team. So if you want to get into it, that’s the best time to get into it; that’s when you find a team, make those connections and really get into [polo]. I think people just assumed I was rich because I played polo, but I played for USC. They provided the horses which we have to care for, and I only had that one horse. [The team and I] were always out there grooming those horses [and] cleaning stalls. There was nothing glamorous about it.”

Work to Ride, founded in 1994 by Lezlie Hiner, is a program with a mission to make polo accessible. This program was created under the belief that children and young adults of all backgrounds deserve a chance to play the sport. In exchange for cleaning stables, helping with horses and keeping optimal grades, kids can learn to play polo for free. Kareem Rosser, ambassador for Work to Ride and Ralph Lauren, published Crossing the Line, a memoir about growing up poor with a determination to be a great polo player, in 2021.

“As a young athlete, I admire those who were willing to fight for their sport,” said student athlete Sophia Impellizeri ‘26. “In a world of so many self centered celebrities and people, it’s amazing to see athletes who were not just willing to fight for their chance to play but for the generations that would come to play after them.”