Valentine’s Day — the day that some go out with their partners and others celebrate with their friends. For me, it’s the day my mom emails a note of gratitude, a health update and a picture of me to the surgeon who operated on my heart exactly 16 years ago.

Because I was born with multiple heart conditions, I have never known my life without surgeries, doctor visits and movement restrictions. Transposition of the great arteries (TGA), coarctation of the aorta (COA), atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), residual heart murmur and valve leakage is the long list I must recite each time I meet someone who asks about the many scars gracing the skin of my chest, stomach and wrists.

TGA and COA are my more complicated defects. TGA occurs when the aorta and pulmonary artery are attached to the wrong sides of the heart, so oxygenated blood keeps cycling back to the lungs, and the blood that circulates through the body is always without oxygen. COA occurs when the aorta has a much smaller circumference than it should, so the heart has to work harder to get the blood through, which results in high blood pressure.

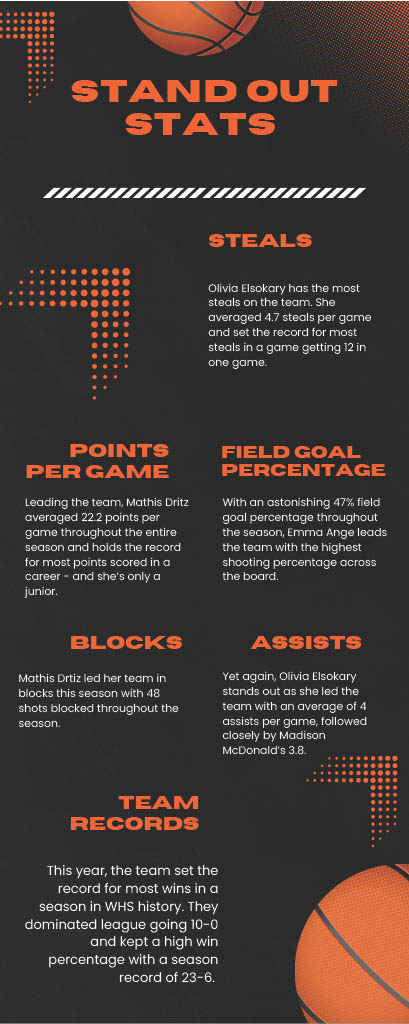

Since my initial surgery at three days old on Feb. 14, 2008, where I had an arterial switch, ASD and VSD closure and aortic arch augmentation, I have had three other procedures for aortic arch coarctation. I had a cardiac catheterization and balloon angioplasty in 2010 when I was two, a cardiac catheterization in 2016 when I was eight and most recently, a cardiac catheterization and stent placement on June 5, 2023.

On April 6, 2023, the middle of the winter season for colorguard, I had a stress test at Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles where I would use a stationary exercise bike while my heart rate, rhythm and blood pressure were monitored. I was stopped when my blood pressure reached 253/47. This means that there was a dangerous amount of pressure in my arteries as blood was pushed but little pressure when my heart relaxed between each beat. For context, my resting blood pressure would usually be around 150/51 while a normal blood pressure for adolescents would be around 120/73.

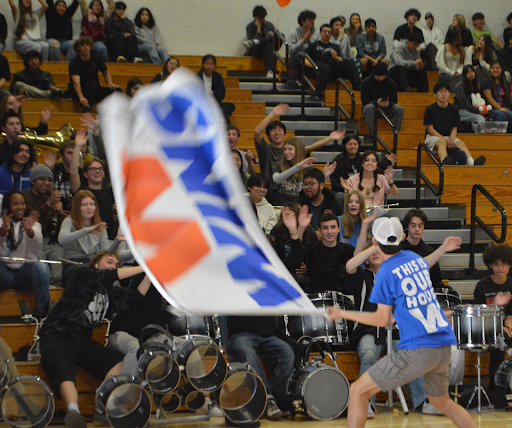

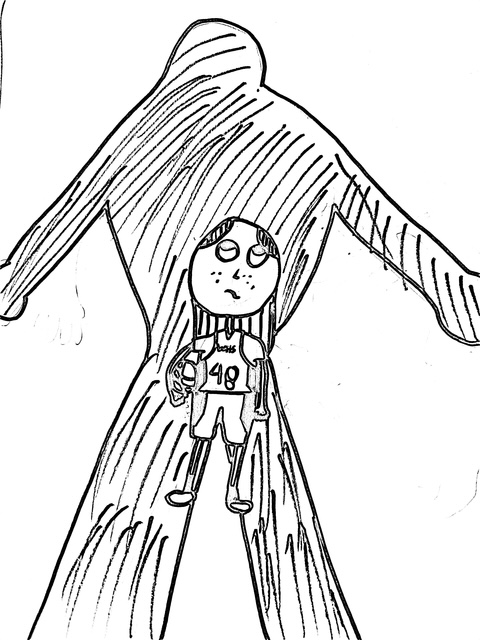

I soon received the news that I would need yet another procedure. I had to step down from the winter show, though I still attended the practices and competitions. All that was safe for me at the time was a 40–second dance sequence at the beginning, after which I would hide behind a prop. What made it even worse for me was that I had a “solo.” I would go to the center of the stage, throw a flag with two rotations, do a spin while it’s in the air and then catch it. While not a big deal to me now when I can catch that same toss in the splits, it was a big deal then, and no longer being able to perform wrecked me even more.

I couldn’t dance, run, play volleyball or move my body in any way that could raise my blood pressure, including walking more than a flight of stairs; I felt lost, sick and useless. It was a sudden change for me.

I attended practices and did nothing but sit on the cold concrete. I had to hear my friends complain about the routines and practice while I so desperately wished I could even do the warmups. Conversations I had previously been part of, I now felt alienated from. I felt like I was in a sort of purgatory, doing nothing but sitting, waiting, watching and wishing. To get from room to room in my house, I used to chassé, piqué turn, tour jeté and pas de bourrée, or as a non–dancer would say, I would jump, spin, leap and waltz. I was now, however, forced to walk; I couldn’t dance like I had done since I was two–years–old. I put away my pointe shoes and my flag, so I wouldn’t be tempted to do those things that brought me so much joy. The absence of these things weighed heavy on my already defective heart.

I finally had my surgery after what felt like years. After recovery, building my stamina back up again was extremely difficult–I’m still struggling to get it back to where it was. I had to take blood thinner medication for six months after the catheterization, so it was easier for the tissue to grow over the metal stent keeping my aorta wide. I eventually stopped taking the medication in December, and now my blood pressure is sitting right where it should.

I still can’t do push–ups, contact sports or run the mile. However, now I can push off with one foot into a series of à la second turns, I can play the sports I used to enjoy and I can run up to my friends to greet them at the top of my driveway when they come over — I can do the things that make me happy.

I still go to the cardiologist more times in a year than any of my peers will in their whole life, I still can’t drink caffeine and I still recite my list of defects often. I am, however, back to my own normal. Although I still, in some aspects, do nothing but sit, wait, watch and wish, I’ve learned to be ok with that.

My whole life I have been called lazy or heard sexist comments when I would sit out of P.E. or take the science building elevator while awaiting my surgery when I was only going to the second floor. I felt the need to explain my whole medical history. One day, however, I realized that they’re not entitled to hear my reason for doing something so innocent. You don’t owe anyone an explanation; it’s not your responsibility to correct other people’s perceptions of you.